Some Recent Paintings

Good news! The Kindle version of my poetry collection just came out.

https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0CW19W5Q2

I am beyond thrilled to announce the publication of my poetry collection A Day Like This.

A printed edition of A Day Like This is now available through the Kelsay Bookstore or

Amazon. For those who prefer an expedited (and more budget-friendly) version, the ebook

will be ready in just a few days and I will make another announcement then. Ratings and

comments, however brief, are deeply appreciated. https://tinyurl.com/27w32z27

“In the title poem of Jean Ryan’s luminous new collection, her speaker sees swallows

slicing the air, observing, ‘Short dark arrows, they never miss, their flight too swift

for error.’ I can’t think of a more apt description for A Day Like This, in which poem

after poem so vivdly penetrates to the core of lived experience. Ryan’s poems have an

ease of movement and transparency of structure I find most enviable. She has a special

gift for finding what remains fresh and particular inside the ancient stuff of poetry.

This is a gorgeous book, powerful and assured, written by a poet who is elegant, concise,

honest, and warmhearted in her approach. I can’t recommend it enough. A quietly masterful

work.”

Erin Belieu, author of Slant Six, Black Box, Come-Hither Honeycomb, and One Above and One Below.

Thought it was time I posted more of my acrylic paintings. I still do many pet

portrait commissions and look forward to the surprise and happiness they bring.

For book recommendations, all you need do is head to Shepherd.com. There you will find lists of book favorites (read in 2023) from participating authors, as well as listings of all around favorite books in a searchable database. What are you interested in reading about? Ben Shepherd has you covered.

For a list of my favorites books read 2023, here is my post. Enjoy!

The last time I cried was a year ago, when I was informed of the passing of a woman I cherished. Death, it seems, is the bar for my tears. Sad movies, stranded polar bears, the plight of children in war torn countries—nothing else brings me to that threshold. Sometimes I try to coax the tears; the closest I get is a slight pull in my throat. I assume that I still can weep, but someone must die to prove it.

At first I thought it could be a side effect of Paxil, which I take for anxiety. I asked others who take this drug and they all said no, they can cry just fine. Given this testimony, the low dosage I require, and the fact that I started on Paxil years before my tears dried up, I doubt my problem is drug-related. In any case, it doesn’t matter: no way am I going back to living with my default mode stuck on panic.

So what did happen to me? It is not uncommon for people to become more jaded as they get older, and I am in fact “older.” Did I glimpse one too many photos of oil-covered seagulls? Have I hardened off in the past few years, turned numb to sadness and madness? I do not feel numb. You know those videos on social media where a dog is drowning, or a baby elephant can’t pull itself out of the mud? Even aware these clips end well, I cannot bear to watch them. And then there’s the minefield of current events. Each morning I open my iPad and tiptoe through the news, avoiding the climate section entirely.

Maybe my body is protecting me, operating on a level beyond my understanding, the way traumatic memories sink into the abyss of subconsciousness. In stemming my tears, my body could simply be trying to survive a little longer by withholding emotions that might undo me. But if this is so, why do I still feel despair and sorrow, and what about the reputed benefits of a good cry, how it detoxifies the body, clears the chakras?

On the scale of human afflictions, not being able to cry wouldn’t even move the needle, and really, is it a problem? Not being able to laugh—now that would be unfortunate. Humor is a stronghold, maybe our last.

Still, this dry-eyed life makes me feel lonely sometimes, and self-conscious, as if I am missing a measure of humanity. Watching some heartbreaking movie, I’ll look over at my wife and see tears streaming down her face as the closing music swells, and something close to jealousy climbs up my chest. She is experiencing something, fully, and I am shut out.

The internet probably clamors with people like me. There must be chat rooms, support groups, therapists who specialize in this disorder, if it can be called that. I wonder how listless I’d have to become to seek such support. My life would have to shrink to the size of an atom. There could be no plants to feed, no backyard birds to watch, no meals to plan, no partner to laugh with, no cat to cuddle, no coffee on the patio, no luck to ponder.

With all this—more than I ever hoped for—maybe there’s just no room left for tears.

This is a memorial painting for a gal in Arkansas, her beloved dog Fred, a three-legged sweetheart. Acrylic paint, natural hardwood back.

Last week I enjoyed a video a friend sent me of gorillas romping in heaps of fallen leaves. Riding the exercise bike a few minutes later, I turned on the television and landed on an enchanting nature show featuring animals at play—lion cubs, penguins, puppies, dolphins. After that, on my way up the stairs, I was ambushed by my spring-crazed cat. He had been hiding behind a door, waiting for me. I took these events as a sign, a reminder that I had a whole day ahead of me in which to have fun, or not.

At the plant nursery where I work there is an arching wooden bridge. In the winter it spans a river of rainwater; in the summer it turns whimsical, serving no function other than to delight the children who are compelled to run over it, again and again. Another attraction are the fountains. Children are charmed by water and will head for it like baby sea turtles. Their joyful shrieks carry across the nursery as they thrust their hands into the basins and splash the water this way and that. Color enchants them, too. They always make a beeline for the water wands, which come in an assortment of delicious colors. Product designers understand that color is fun, and even adults can’t resist that rainbow display. We sell a lot of water wands.

Children are masters of play. I’ve often wondered why this is so, why we lose the capacity for fun as we get older. We have our grown-up games of course—Scrabble and poker, Wii and Xbox, tennis and bowling. But these are games with an end point, a goal. Even individual sports like hang-gliding or cliff jumping require planning and risk assessment, a competition with oneself.

Children don’t pause to consider themselves; they just plunge into whatever catches their attention. They do not know that being alive means being in peril. They have no idea that their chances are slimming, that summers are not long, that one day they won’t be here. When they start skipping, when they make stone soup, when they build forts out of chairs and blankets, they are living in the only realm they will ever own. Running without reins, they are free because they don’t know it.

While we may no longer feel the urge to build forts or splash in fountains, we adults still lose ourselves now and then. Alone in our homes, we might break out in dance, or grab a spatula and start singing into it. In quieter moments, we can disappear into our passions: fossil collecting, product design, painting. As a writer, I lose myself not only in composition, but in research as well. There are many way to escape the tyranny of time, if only for a few hours.

It is said that a person who is living well makes no distinction between her work and her play, and this is certainly true for those lucky enough to love their jobs. Most of us can’t make that claim. We labor to pay the bills, and then we labor at home, and what free time we have is spent driving from one store or business to another. After a few months of this, we reward ourselves with a vacation that never feels adequate because we have leveraged too much on it.

I’m wondering if we can trick our stodgy selves by wringing more joy out of our daily lives, if, like children, we could make our own fun? We could start small, maybe with accessories, adding a scarf, a lapel pin. We could pour our coffee into china instead of a mug. Taking a cue from Martha Stewart, we could decorate the dining room table with fall leaves and fruit. We could smile at everyone we encounter and see what they do. We could make it a game.

There’s a woman in town who drives an old Cadillac on which she has glued hundreds of tiny toys. There is a couple down the street who have turned their front yard into a fairyland of handmade stone castles. The woman next door takes photos of neighborhood dogs, then turns them into Christmas ornaments she gives to the owners.

How hard could it be to have a little more fun each day? A child can do it.

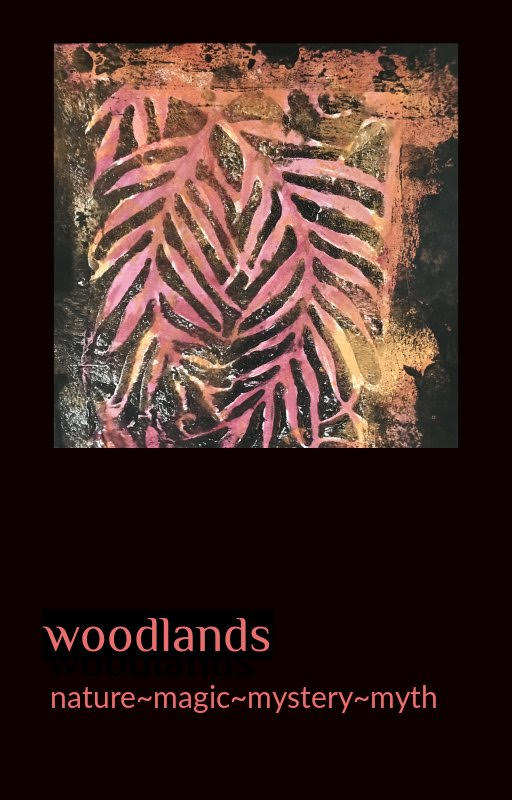

I give my deep thanks to the editors of Woodlands nature~magic~mystery~myth for including my poem “Lichen” and my essay “Lyme Ticks and Ladybugs” in this wondrous new anthology. A perfect tonic for the busy holiday season, Woodlands is now available on Amazon. Stoke the fire, curl up your sofa, and enjoy this treasury of nature writing.