More Nature Paintings

Thought it was time I posted more of my acrylic paintings. I still do many pet

portrait commissions and look forward to the surprise and happiness they bring.

Thought it was time I posted more of my acrylic paintings. I still do many pet

portrait commissions and look forward to the surprise and happiness they bring.

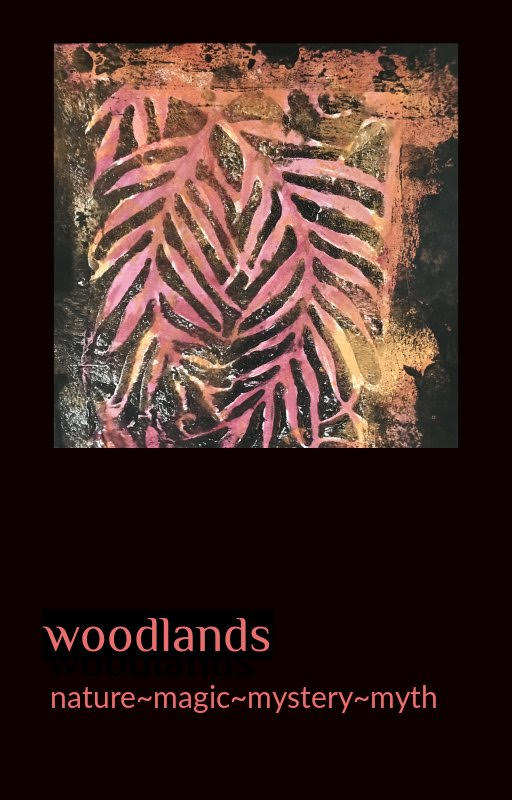

I give my deep thanks to the editors of Woodlands nature~magic~mystery~myth for including my poem “Lichen” and my essay “Lyme Ticks and Ladybugs” in this wondrous new anthology. A perfect tonic for the busy holiday season, Woodlands is now available on Amazon. Stoke the fire, curl up your sofa, and enjoy this treasury of nature writing.

Do animals think? Countless experiments have been undertaken to answer this question and the consensus is: Yes, they do.

I guess I’ve always considered this answer fairly obvious. How would creatures survive if they couldn’t evaluate situations and make appropriate decisions? Lionesses form collective hunts. Crows drop their walnuts into the path of vehicles. Beavers adjust the logs in their dams to control water levels. Plovers fake a broken wing to lure predators away from their nests. God knows what chimps and parrots are capable of.

When they are not trying to acquire food or protect their young or get attention, what do animals think about? When a lion has finished his dinner and is gazing out on the African plain, what is going on in his feline mind?

The sloth. Now there’s an animal with plenty of time to mull things over. Looking at a photo of a sloth—the big eyes, the gently smiling mouth—I am certain that something astonishing is going on in that short, flat head.

Sloths spend their lives hanging upside down from tree branches. In this pose, they eat, sleep, mate, bear young and die; even after death a sloth may hang from a branch for days, as if the divide between death and its sedentary life does not much matter. The world’s slowest mammal—an average clip is six feet a minute— sloths move only when necessary so as not to tax their minimal musculature. On the ground they are awkward and vulnerable, long polished claws serving as their only defense. For this reason, they stay in the trees, descending just once a week to urinate and defecate, digging a hole and covering it up afterward. While slowness might be considered a detriment to survival, this trait is actually an advantage for the sloth, whose lack of motion draws no attention. Another advantage of a slow pace is the chance it gives other life forms to take hold: algae blooms freely on sloths, serving as perfect jungle camouflage, as well as a handy food source.

Nocturnal creatures, sloths forage on their trees from dusk to dawn, methodically eating the fruit, leaves and bark. This roughage is then effortlessly digested, albeit slowly, with the help of multi-compartmentalized stomachs that comprise two-thirds of the animals’ body-weight.

Once a year the female lets out a few loud shrieks, which the male dutifully answers, and after great time and effort, they manage to arrive on the same branch. The mating itself occurs over a period of several minutes, and in what seems to be a tender fashion—sloths are the only mammals other than bonobo apes and humans that mate face-to-face. The baby sloth appears six months later and spends much of its first year clinging its mother.

Research shows that sloths spend about ten hours a day sleeping. In the hours the animal is awake but inactive, it hangs from its limb and regards the jungle canopy, moving its flexible neck in increments, blinking now and then. Hidden among the leaves, making no sound or movement, these mute little beasts seem to want just one thing: to be undiscovered.

The two main emotions in life are love and fear, and certainly there is ample evidence that animals feel both. I imagine that when the shadow of a raptor passes overhead, a sloth cringes in fear. What about the lesser emotions, the ones that don’t serve us—like worry? Does a sloth, with all that time he has, worry about eagles and jaguars? Or does he have more productive thoughts, which part of the tree he’ll dine on that night? Or is he, is some deep animal way, simply enjoying himself, his mind a movie screen of pleasant images: leaves, sky, dappled light. When thoughts are not needed, maybe animals are not burdened with them.

It is estimated that people have 60,000 thoughts a day, a figure not as impressive as it sounds. These 60,000 thoughts are the same ones we had yesterday and the same ones we’ll have tomorrow. In our day to day lives, we are not much good at thinking out of the box. A sloth hangs in one tree all its life and, other than single visit from a single mate, has no company. With this scant stimulation, I wonder how many separate daily thoughts a sloth has. A hundred? Twenty? I would trade my 60,000 for a glimpse of them.

It’s been awhile since I posted any artwork, so here are a few photos of some recent work, most of it in collaboration with my woodworker/scroll saw maestro wife. I am doing more and more commissioned pet portraits–canines are much in demand.

Have you ever wished there were a way to find the best books on a particular subject? Welcome to Ben Fox’s Best Books series, a website for finding and discovering stand-out works on a delightful variety of interests. Many thanks to Mr. Fox for including my book, Survival Skills, in this amazing project, along with five other outstanding works sure to please animals lovers everywhere.

I wish to thank the wonderful writer and editor Mark McNease for featuring four essays from my collection “Strange Company” on his podcast. Mark has published three of my books and his support and encouragement have been invaluable. Please visit his website to read his blog posts, enjoy his podcasts, and find information on his many mystery novels.

To listen to four selections from my book “Strange Company” please follow this link to Mark’s podcast site. After a brief introduction, you will hear the beautiful voice of Nikiya Palombi as she perfectly captures the mood of the pieces. Enjoy!

These are acrylic paintings on salvaged wood. Some are scrolled out and painted, others are painted directly onto the wood. Contact me if you have a beloved pet you would like to immortalize.

Surging dolphins.

Ospreys carrying dinner.

Fried shrimp picnics on the banks of a bayou.

Box turtles crossing the yard.

Tree frogs on the window pane.

Corn snakes in the squash.

The size of grasshoppers.

How tall my basil grows.

The end of summer.

And the Make America Green Again

bumper sticker I saw yesterday

on a car whose driver I’d pay to meet.