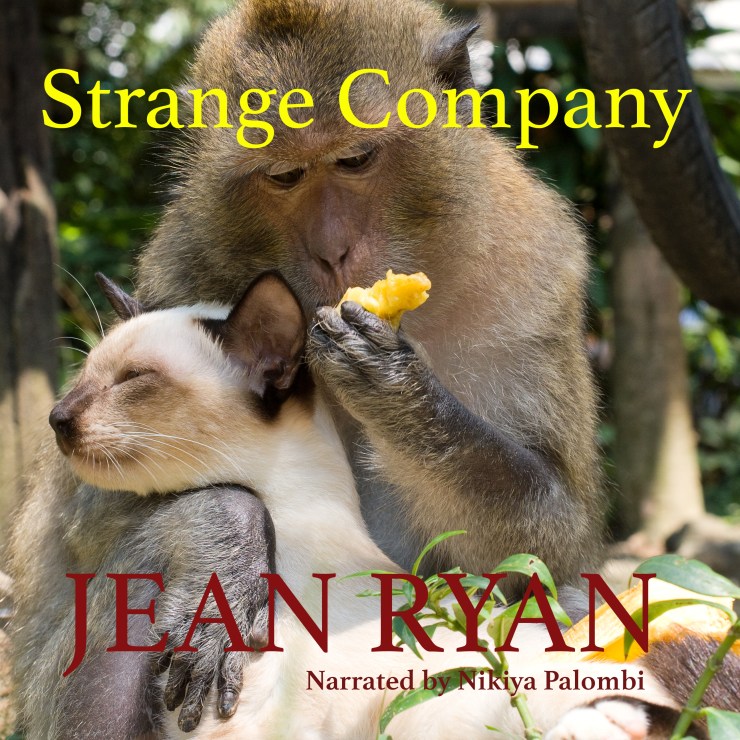

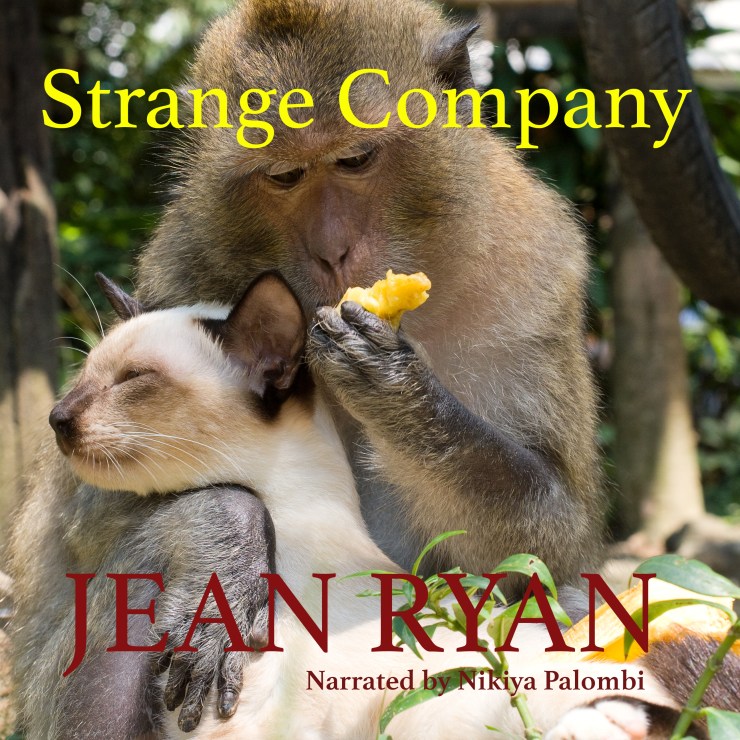

Audio Sample from Strange Company

Here is an audio sample from my new essay collection, Strange Company. Enjoy the beautiful voice of Nikiya Palombi.

Here is an audio sample from my new essay collection, Strange Company. Enjoy the beautiful voice of Nikiya Palombi.

As most of you know, I am a writer (and I say that with the deepest humility). Because I believe that everyone should give the world whatever skills they possess, modest or monumental, I have gathered twenty of my brief nature essays into a collection called Strange Company, which is now available as an eBook for $2.99. If you don’t have a tablet, you can download the Kindle app or Adobe Digital Editions to your computer.

Do lizards fall in love? What do sloths think about all day? Why is the blood of a horseshoe crab so valuable? Do starlings flock for fun? Do turtles ever grow bored with their long lives? Can snails be fearless? Can a parrot be a therapist?

These are some of the questions that keep me up at night. Maybe you’re likewise in awe of the natural world, or maybe you’d just like a breather from daily events. Either way, $2.99 is a pretty good deal, right? And you even get photos 🙂

Today I wish to give deep thanks to editor Ilana Masad for featuring “A Sea Change” in The Other Stories podcast. This story is part of my collection SURVIVAL SKILLS, published by Ashland Creek Press.

Photo credit: <a href=”https://www.flickr.com/photos/daugaard/2687998731/”>DaugaardDK</a> via <a href=”http://foter.com/”>Foter.com</a> / <a href=”http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/”>CC BY-NC-SA</a>

“Paradise” is included in my collection SURVIVAL SKILLS. Here’s a quick look at Max, the star of the story.

Anyone who’s ever owned a parrot will know why I cherish my newfound peace and quiet. Parrots scream at dawn and dusk (ancestral behavior they can’t help), and at intervals throughout the day just for the hell of it. I can’t tell you how many dreams I’ve been yanked out of, how much coffee or wine I’ve spilled on the carpet, all because of Max. And what really irked me was Kelly’s insistence that we never, NEVER startle him. Undue stress, she claimed, killed more pet birds than any other factor, and so we had to give a certain soft whistle—one high note, one low―every time we approached his room lest our sudden appearance disturb his reverie.

No captive bird has it better than Max. Back in Shelburne, in the farmhouse he shares with Kelly, Max has his own room, with jungle scenes painted on the walls and two large windows that give him a view of the dogwoods and the pond and the distant green mountains. He has a variety of free-standing perches to suit his rapidly shifting moods and a wire-mesh enclosure that takes up nearly a third of the room. Inside this cage are his stylish water and food bowls, several large branches from local trees and usually four or five toys Kelly finds at yard sales. These he bites or claws beyond recognition; if he is given something he can’t destroy he shoves it into a corner. Of course she must be careful about lead paints and glues. Captive birds are never far from peril. I learned that the first week I was there, when I heated up a pan to make an omelet and Kelly yanked it off the stove and doused it with water. Didn’t I know, she scolded, that the fumes from an over-hot Teflon pan could kill a parrot in minutes?

It was exhausting living with that bird, meeting his needs, second-guessing his wants. Kelly said I didn’t have the right attitude toward Max, which may have been true. I never did tell her what I really thought: that birds make lousy pets. Dogs and cats are pets. Everything else belongs in the sky or the water or the desert it came from. So right away I felt a little sorry for Max, even when I learned he was captive bred and able to fly, even when I told myself he was probably healthier and possibly happier living in his painted jungle, for what would he face in Guatemala but poachers and pythons and shrinking habitat? Even acknowledging their success―14 years of cohabitation―I couldn’t help seeing Max as a bird beguiled.

Maybe he sensed my pity and resented it. Or maybe he didn’t like the texture of my hair or the way I smelled. Maybe my voiced irked him. Maybe I reminded him of someone else. Whatever his reason, Max didn’t like me, no matter how hard I tried to please him. You’re probably thinking he was jealous, that he wanted Kelly all to himself; I thought that too, at first. Then I noticed how he welcomed the arrival of our friends and how charmed he was by Suzanne, Kelly’s former live-in girlfriend. I tried not to take it personally, but that bird was so shrewd he had me worried.

Photo credit: <a href=”https://www.flickr.com/photos/pokerbrit/9010421285/”>Steve Wilson – over 8 million views Thanks !!</a> via <a href=”http://foter.com/”>Foter.com</a> / <a href=”http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/”>CC BY</a>

The quiet world of cuttlefish.

“I lingered in front of the kelp forest, eerily beautiful in the morning light, and as I watched the leathery brown ribbons swaying in the currents, the chains of bubbles and the silver fish, I could imagine the relief a diver must feel: a single plunge, and all history is banished, blame lifted, anguish ended.”

Excerpt from “A Sea Change,” one of the stories in SURVIVAL SKILLS

A big thank you to my human editor Midge Raymond for kindly inviting me to participate in her “Cat Editors” column. Here is the latest post, featuring me and Tango.

Please look for Midge’s new book, My Last Continent, coming from Scribner in June 2016.

Having written this story, http://bluelakereview.weebly.com/manatee-gardens.html, I love this short video. https://www.facebook.com/supweeki/videos/874149955997865/?fref=nf