More Nature Paintings

Thought it was time I posted more of my acrylic paintings. I still do many pet

portrait commissions and look forward to the surprise and happiness they bring.

Thought it was time I posted more of my acrylic paintings. I still do many pet

portrait commissions and look forward to the surprise and happiness they bring.

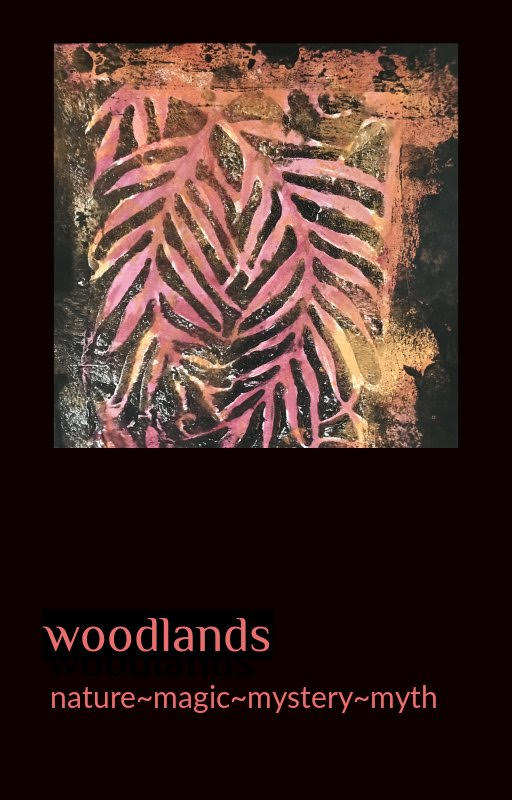

I give my deep thanks to the editors of Woodlands nature~magic~mystery~myth for including my poem “Lichen” and my essay “Lyme Ticks and Ladybugs” in this wondrous new anthology. A perfect tonic for the busy holiday season, Woodlands is now available on Amazon. Stoke the fire, curl up your sofa, and enjoy this treasury of nature writing.

How we view time can be a source of comfort or pain. Many people, particularly eastern cultures, adhere to the belief that we live any number of lives: time is seen as cyclical and forgiving. Westerners tend to see time as linear, something we use up, something we never have enough of.

Whatever our beliefs, we all know that the lives we are living now will one day end. This knowledge is the ultimate spoiler, the price we pay for having a neocortex. Other animals are not saddled with this awareness—at least I assume, I hope, they are not.

In 1777 the British explorer Captain Cook gave a newly hatched tortoise to a royal family in Polynesia, who kept the creature as a pet until it died of natural causes 188 years later. That turtle pulled its heavy self across the ground, presumably the same well-worn ground, for 68,620 days. Was it weary by then? Bored? Might it have opted for a life half as long?

On the other end of the spectrum is the mayfly, a creature whose adult life amounts to less than a day; in some species, just a few minutes. The larval versions, naiads, can live up to a year, during which they hide in aquatic debris and progress through several stages—instars—before growing a pair of wings and becoming immature adults. The winged juveniles last no longer than the final version and are not sexually viable until a few hours later, when they emerge from their last molt with features unique in the insect world, paired genitals: two penises for the males and two gonopores for the females. They do not feed: their mouths are useless and their digestive tracks are filled with air. This day, their first and last on earth, all they do is mate—little wonder our creator doubled up on their genitalia.

Like locusts, mayflies “hatch” in stupendous numbers, trillions at a time. The males begin swarming over a river and the females fly into this mass. With specialized legs, the male grab a female and copulation takes place in mid-air, after which the female falls to the water’s surface and lays her eggs before dying. The spent females cover the water, providing a feast for the fish below. The males fly off to die on land, a boon to local birds.

Even the waiting wildlife cannot keep pace with these mayfly windfalls, and in some municipalities snow plows are deployed to clear away the mountains of corpses. While Americans consider mayflies a nuisance, tribes in Africa make nutritious patties out of them.

It would seem that a mayfly’s fleeting life amounts to nothing more than sustenance for larger creatures. Mayflies, all 2500 species of them, are designed as sacrifices, put here for the greater good. Twenty-four hours is all the time they are given and all the time they need.

The ancient Greeks had a saying:

“There is not a short life or a long life.

There is only the life that you have,

and the life you have is the life you are given,

the life you work with.

It has its own shape, describes its own arc, and is perfect.”

A whole life in one day. It must be glorious.

In the spring of 2013, the seventeen-year cicadas, called Magicicadas, emerged from their burrows along the eastern seaboard. This was Brood II and involved seven states. In 2012 Brood I emerged in Virginia, West Virginia and Tennessee. Brood VIII appeared right on schedule in west Pennsylvania in 2019.

I love this chart—it’s like a treasure map. How wonderful to know that if I show up in a woods in southern Wisconsin in the spring of 2024, I will witness the emergence of millions of cicadas. I would like to be there, peering at the ground, when the very first one sticks his head up. “Welcome,” I would say. “Welcome to this world.”

When the nymphs emerge, their bodies are soft and cave-white. I imagine they are blind, too, which might explain why they show up after sunset: sunlight must be shocking after seventeen years underground. The first thing they do is find a bit of vegetation to rest on while they complete a final molt that takes them into adulthood. In a week’s time, their exoskeletons have hardened and darkened, and they have grown transparent wings with orange veins. Their eyes, now quite large, are bright red. Like stubborn ghosts, the skins of their youth remain in the places they were.

The males, seeking mates, begin contracting their abdomens to make a series of loud buzzing and clicking noises. Often they form choruses high in the sunlit branches of trees, and their considerable racket attracts females of the same species. While the females don’t sing, they answer the males with a noise of their own, a movement called a wing flick, which can vary from a rustle to a sharp pop. Eventually they all find each other and a mass mating occurs overhead, after which the females cut slits in twigs and lay their several hundred eggs. Six weeks later the eggs hatch, releasing nymphs the size of ants that fall to the ground and immediately burrow in. For nearly two decades these pale bugs tunnel through a black world, sucking tree root sap as needed and growing ever so slowly. No one knows why they stay hidden for so long, or what finally beckons them skyward all at once.

Cicadas don’t live long as adults, not even long enough to see their progeny. In a month’s time, they sing, mate, lay eggs and die, leaving an immense litter of dry husks. So many of them come into the world that even after the birds and rodents are satiated, the population remains intact.

I suppose those four weeks of glory is the point of a cicada’s life, but I wonder about the young, who live seventeen years in silence, impervious to cold and wind and noise. I see them tunneling away, no clue there’s another world waiting, no need to know anything but the next quarter inch. It seems a kindness, all that time to be young.

I wish to thank the wonderful writer and editor Mark McNease for featuring four essays from my collection “Strange Company” on his podcast. Mark has published three of my books and his support and encouragement have been invaluable. Please visit his website to read his blog posts, enjoy his podcasts, and find information on his many mystery novels.

To listen to four selections from my book “Strange Company” please follow this link to Mark’s podcast site. After a brief introduction, you will hear the beautiful voice of Nikiya Palombi as she perfectly captures the mood of the pieces. Enjoy!

For all you nature lovers, the Kindle version of Strange Company, my collection of nature essays is on sale at Amazon. This is a light-hearted look at some of our most curious beasts, a cozy read for these cold winter months. Here is an excerpt from “Consider the Sloth.”

“The two main emotions in life are love and fear, and certainly there is ample evidence that animals feel both. I imagine that when the shadow of a raptor passes overhead, a sloth cringes in fear. What about the lesser emotions, the ones that don’t serve us—like worry? Does a sloth, with all that time he has, worry about eagles and jaguars? Or does he have more productive thoughts, which part of the tree he’ll dine on that night? Or is he, in some deep animal way, simply enjoying himself, his mind a movie screen of pleasant images: leaves, sky, dappled light. When thoughts are not needed, maybe animals are not burdened with them.

It is estimated that people have sixty thousand thoughts a day, a figure not as impressive as it sounds. These sixty thousand thoughts are the same ones we had yesterday and the same ones we’ll have tomorrow. In our day-to-day lives, we are not much good at thinking out of the box. A sloth hangs in one tree all its life and has no company other than the mate it couples with every fourteen months or so. With this scant stimulation, I wonder how many separate daily thoughts a sloth has. One hundred? Twenty? Three? I would trade my sixty thousand for a glimpse of them.”

Greatness

An osprey dives over and over,

as many times as it takes to stay alive

and become incidentally superb.

Driving down the road near my house

I see them flying, a stunned fish in their claws,

as if nothing could be more ordinary

than a bird bringing home dinner.

Wings or brains,

we work with what we have.

I can’t snatch a meal from the ocean

at 50 miles an hour,

but I can plant a garden,

make stories out of thin air,

learn the difference

between an aspen and an alder.

Minute by minute,

even I can be splendid.

A green lacewing. Isn’t it stunning? The looping cellophane wings, the extravagant antennae, the eyes a pair of shining beads. And that streamlined body–in all the world, could there be a truer green? Imagine taking flight with those diaphanous wings, sailing into darkness with see-through tackle. Maybe, with lives this brief, beauty pre-empts sturdiness.

Adult lacewings are nocturnal and fairly passive; most feed on nectar, pollen and honeydew. At some point during their four-to six-week lives, they find a mate, touch antennae, mingle mouthparts, and finally join abdomens, jerking and vibrating in a vertical position. The female soon lays 100 to 200 eggs on foliage, ideally with plenty of aphids nearby. Each dainty white egg is secured at the end of a filament about a half inch in length. After a few days the eggs hatch, molt, and the emerging larvae climb up the stalks and into the sunshine. Immediately they start feasting on whatever they can find: aphids, mites, caterpillars, other small bugs and eggs. These creatures are so proficient at dispatching aphids that lacewing eggs are shipped to gardeners and farmers for use as biological pest control.

Unlike humans, who are most comely in their youth, lacewing larvae are not what we’d call attractive. Their humpback bodies are swollen in the middle, and tufts of bristles protrude from their sides. These bristles are neither armor nor adornment. They are there to help secure dead victims and other debris to the backs of the larvae. As the gruesome collection grows, it serves as camouflage from birds and other predators, while offering the host cover for hunting.

Lacewing larvae tend to swing their heads from side to side as they search for food, seizing what they find with their strong mandibles and injecting it with paralyzing venom. The hollow jaws then draw out the body’s fluid, after which the corpse is tossed onto the heap of other luckless prey. Occasionally these rapacious predators, also called aphid lions and aphid wolves, will even bite humans. In two or three weeks nature cues them to stop eating and start spinning cocoons, from which adult lacewings appear five days later to repeat the cycle.

Fearsome youth or fragile beauty–makes no difference to the common lacewing, who is always both, forever coming, forever going, a crawler with notions of flight, a flyer with flashbacks of sunshine.

Photo by mbrochh on Foter.com / CC BY-SA

Photo by dreed41 on Foter.com / CC BY-NC-SA

Photo by Pasha Kirillov on Foter.com / CC BY-SA

Photo by Marcello Consolo on Foter.com / CC BY-NC-SA

While the South Napa Earthquake was a meh compared to grand scale disasters, Hurricane Harvey has reminded me of the lessons I learned that day, which I am re-posting now. My deep sympathy to the victims and survivors of this catastrophic storm. In its wake, may love and good will continue to bloom.

1) You will never look at your home the same way again.

Homes are wounded, some more deeply than others; in fifteen seconds they have aged two decades. Most will need long-term care, the sort of attention that involves forgiveness. With enough money and patience, you can battle the mounting flaws. Alternatively, you can turn tender and live in peace with the wear and tear. You can accept your aging home the same way you accept your imperfect body.

2) Nature will win.

You know this now. Nature’s blows are indiscriminate and nonnegotiable. You have seen photos of the Mount St. Helens eruption, footage from Hurricane Katrina, but until you have been caught inside the roar yourself, flung like a rag doll inside your splintering house, you are not intimate with Mother Nature. Having survived one of her surges, you will love her no less and trust her no more.

3) You are not safe.

Security is an impossible ideal. This does not mean that you should go running full-speed down the knife edge of your life. Neglecting your belongings; falling into drink, debt or despair—these are not answers to your vulnerable condition. Instead, you must shore up what you can and live with what you love: people, plants, animals, objects. However fragile or fleeting, whatever you hold dear graces your days and justifies its place in your life.

My deep thanks to Ti at Book Chatter for this review of Strange Company. Ti usually reviews works of fiction, particularly novels, and I admire her penetrating insights and gentle guidance. I appreciate the kindness she offered me in accepting this essay collection for review.

<