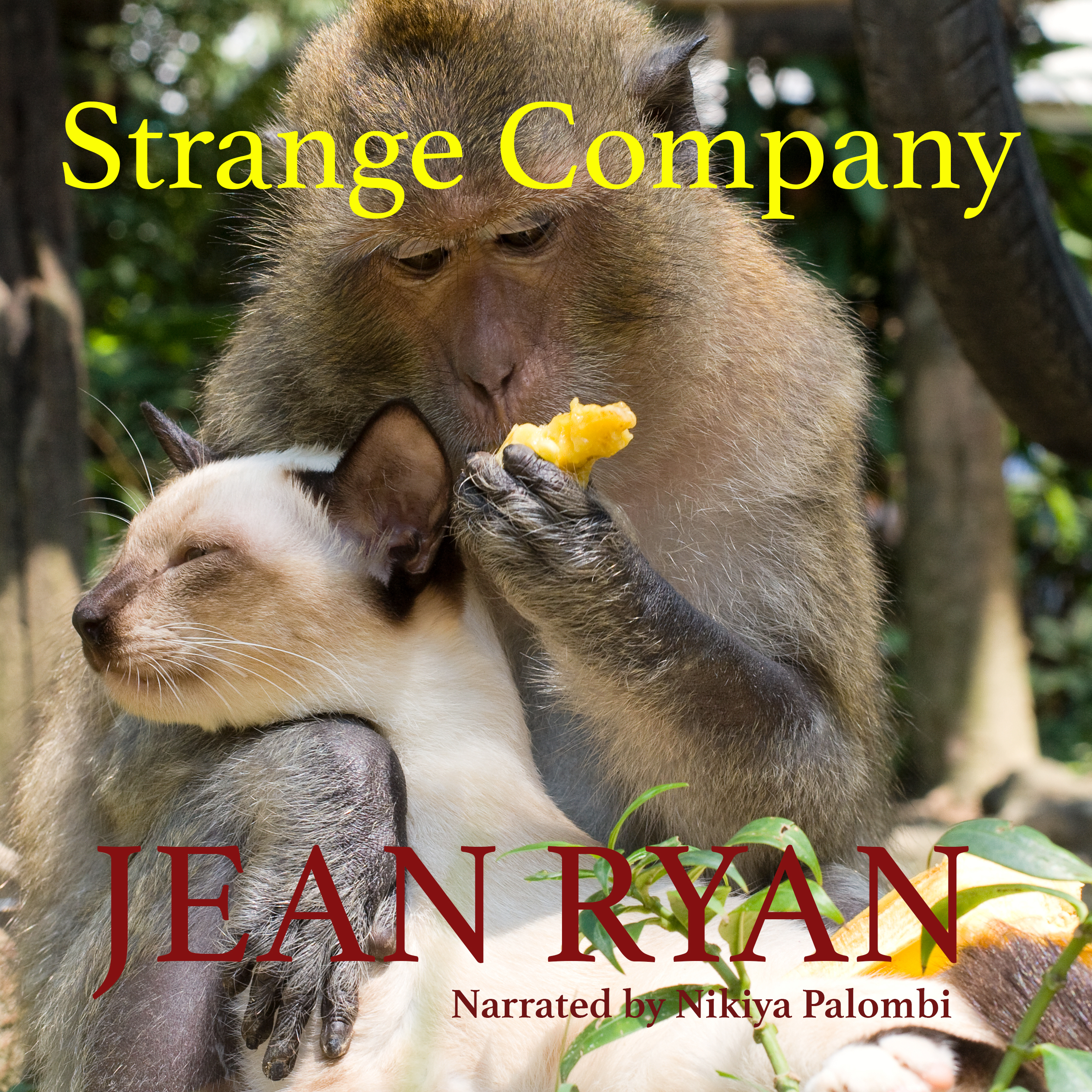

Great Deal On Strange Company!

For all you nature lovers, the Kindle version of Strange Company, my collection of nature essays is on sale at Amazon. This is a light-hearted look at some of our most curious beasts, a cozy read for these cold winter months. Here is an excerpt from “Consider the Sloth.”

“The two main emotions in life are love and fear, and certainly there is ample evidence that animals feel both. I imagine that when the shadow of a raptor passes overhead, a sloth cringes in fear. What about the lesser emotions, the ones that don’t serve us—like worry? Does a sloth, with all that time he has, worry about eagles and jaguars? Or does he have more productive thoughts, which part of the tree he’ll dine on that night? Or is he, in some deep animal way, simply enjoying himself, his mind a movie screen of pleasant images: leaves, sky, dappled light. When thoughts are not needed, maybe animals are not burdened with them.

It is estimated that people have sixty thousand thoughts a day, a figure not as impressive as it sounds. These sixty thousand thoughts are the same ones we had yesterday and the same ones we’ll have tomorrow. In our day-to-day lives, we are not much good at thinking out of the box. A sloth hangs in one tree all its life and has no company other than the mate it couples with every fourteen months or so. With this scant stimulation, I wonder how many separate daily thoughts a sloth has. One hundred? Twenty? Three? I would trade my sixty thousand for a glimpse of them.”